A few weeks ago I attended a fabulous talk on fire ecology hosted by the California Native Plant Society. The speaker was Dr. Sasha Berleman, who earned her PhD at Berkeley and focused her research on the use of prescribed fire in California. Sasha gave a thorough overview of the history of fire in our region, the ecological effects of the recent wildfires, and thoughts for the future. I left the talk with some much-needed context for what the North Bay had just endured. Below I’ll highlight some of my key takeaways from her great talk.

Context for Fire

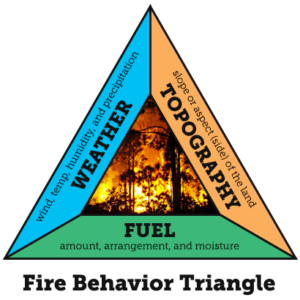

We started with a basic explanation of what’s referred to as the fire behavior triangle, which involves the three main determining factors of wildfire. The first is topography, which encompasses both how steep a slope is (and therefore how fast fire can travel), as well as the slope’s aspect (which direction it faces). The second arm of the triangle is weather. In our Mediterranean climate, our landscape is adapted to fire. Our late summer/early fall ‘Diablo Winds’ are strong, dry winds that sweep from the Northeast towards the shore. Northeast-facing canyons act as funnels channeling fire to the southwest, as we all experienced on October 8th.

We started with a basic explanation of what’s referred to as the fire behavior triangle, which involves the three main determining factors of wildfire. The first is topography, which encompasses both how steep a slope is (and therefore how fast fire can travel), as well as the slope’s aspect (which direction it faces). The second arm of the triangle is weather. In our Mediterranean climate, our landscape is adapted to fire. Our late summer/early fall ‘Diablo Winds’ are strong, dry winds that sweep from the Northeast towards the shore. Northeast-facing canyons act as funnels channeling fire to the southwest, as we all experienced on October 8th.

The third arm of the fire behavior triangle is fuel, and this is the only factor that we as humans directly control. This comes into play as we consider what we’re doing to manage (or fail to manage) our forests.

Historical Context: Our Changing Relationship With Fire

It was interesting for me to think about how dramatically our relationship to fire has changed in the past century. We didn’t always have the fraught relationship with fire that we have today. Native Americans used to use fire as a key ecological maintenance strategy.

In fact, before 1800, it’s estimated that up to 8 million acres burned annually in California. This means that during most of the summer and fall, the sky was likely filled with smoke. Imagine!. Much of this fire activity was actually managed burns used by Native American populations as they lived closely with and actively managed the landscape. They used fire for countless reasons, including to clear space for encampments, to clear walking paths, to encourage new growth in the chaparral to draw deer for hunting, and, to encourage new growth in the form of supple canes that lent themselves to basket weaving.

In fact, before 1800, it’s estimated that up to 8 million acres burned annually in California. This means that during most of the summer and fall, the sky was likely filled with smoke. Imagine!. Much of this fire activity was actually managed burns used by Native American populations as they lived closely with and actively managed the landscape. They used fire for countless reasons, including to clear space for encampments, to clear walking paths, to encourage new growth in the chaparral to draw deer for hunting, and, to encourage new growth in the form of supple canes that lent themselves to basket weaving.

It wasn’t until much later that our culture in the American West moved into the mode of fire suppression. In the post-war era, people began moving west and were terrified by the wildfires they saw out here. This in combination with the growth of the lumber industry meant that fire started to be seen as a force to be fought.

This represented a huge change in our relationship to the land and subsequently, to the landscape itself. Sasha showed pictures in her talk of one ranger station in the Sierras 100 years ago vs. today. In the old picture, the station sits in an almost treeless grassy landscape, whereas the picture today shows the station absolutely surrounded by chaparral trees. The contrast was astounding, particularly considering that the change is due to the recent lack of fire. By suppressing fire, we have dramatically increased the amount of chaparral in the landscape.

Back to The Fuel Factor

Sasha then moved on to make the case that we have the power to start managing the fuel factor more like we did in the past. This past May, she managed three prescribed burns at Bouverie Preserve in Kenwood, encompassing a combined 20 acres. The results of these burns were astounding.

Sasha then moved on to make the case that we have the power to start managing the fuel factor more like we did in the past. This past May, she managed three prescribed burns at Bouverie Preserve in Kenwood, encompassing a combined 20 acres. The results of these burns were astounding.

First of all, in the wake of the October fires, it was shown that none of her prescribed burn areas reignited, and they, in fact, slowed the path of the fires. Interestingly, there was a strip of oak woodland that was too wet to ignite during the prescribed burn in May, and it acted as a natural barrier and stopped the fire as planned. They had wanted to return in fall to perform a burn, but the wildfires did it for them instead. The result was a very slow-moving understory fire in the midst of huge fast fires, creating a prescribed burn condition in the midst of the wildfires.

Ecological Adaptations

Sasha continued to explain the ways in which our landscape is used to fire and even needs it. Oaks are highly adapted to fire. They boast broad, fire-resistant leaves that they drop in fall. Many Coast Live Oaks can, in fact, resist fire, as we may have seen in the wake of the October fires in some areas.

Putting it simply, oaks need fire under their canopy. For one example, she pointed us towards the acorn weevil. This is a native pest that works its way into acorns, rendering them unable to sprout, naturally limiting the number of oaks growing in any area to a healthy number. When we drive down their numbers with fire, we essentially allow and encourage acorns to sprout.

Oak woodlands aren’t even particularly sustainable without fire. In the absence of fire every 5 – 25 years or so (which seems to be the target interval to which our forests are adapted), other small encroaching trees, including Bay Laurel, are allowed to grow and mature in numbers. These smaller, more flammable trees compete with oaks and prohibit them from growing into the old, flame-resistant elders of the forest they want to become. Without fire, we’d be unlikely to have our beautiful 300 – 500 year old oaks that dot the landscape. In fact, without fire, we miss our opportunity to control the growth of the encroaching trees, as at about 12 years old they become too old to be taken out by fire.

A New Perspective

Sasha ended by really drilling in the fact that many of our systems are adapted to high-severity fire. While the recent fires were undoubtedly huge human disasters, they were not necessarily ecological ones. “You don’t need to be sad when you drive by huge black patches of earth in our North Bay landscape because many of these plants, in fact, want to be burned to a crisp.” I have to say, this did make me feel better.

Sasha ended by really drilling in the fact that many of our systems are adapted to high-severity fire. While the recent fires were undoubtedly huge human disasters, they were not necessarily ecological ones. “You don’t need to be sad when you drive by huge black patches of earth in our North Bay landscape because many of these plants, in fact, want to be burned to a crisp.” I have to say, this did make me feel better.

Ecosystems want to be tended with fire the way they were for thousands of years. They have evolved to respond to fire and know what to do. When you get up close to these black patches of scorched earth, you see that there’s actually a lot of activity. They’re full of sprouting rare plants and flowers that show up in chaparral after fire. If nothing else, we can expect a magnificent wildflower season in our landscape.

My thanks to Sasha and the Milo Baker chapter of the California Native Plant Society for a fabulous presentation.

Family

Family